Mary Flanagan pushes the boundaries of medium and genre across writing, visual arts, and design to innovate in these fields with a critical play centered approach. Her groundbreaking explorations across the arts and sciences represent a novel use of methods and tools that bind research with introspective cultural production. As an artist, her collection of over 20 major works range from game-inspired systems to computer viruses, embodied interfaces to interactive texts; these works are exhibited internationally. As a scholar interested in how human values are in play across technologies and systems, Flanagan has written more than 20 critical essays and chapters on games, empathy, gender and digital representation, art and technology, and responsible design. Her three books in English include Critical Play (2009) with MIT Press. Flanagan founded the Tiltfactor game research laboratory in 2003, where researchers study and make social games, urban games, and software in a rigorous theory/practice environment. Flanagan’s work has been supported by grants and commissions including The British Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the ACLS, and the National Science Foundation. Flanagan is the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor in Digital Humanities at Dartmouth College.

Liveblog

The question that motivates Mary is:

“How do we move people to be an effective force for change, for their own welfare and the welfare of others?”

She begins by noting that there’s a huge push towards gamification. So much that “I don’t want to say the G-word.” We’re going to be healthier, better people. Mary likes to break this down: how will it really make us better? How do we move people to make changes for themselves in a non-coercive way?

She’ll tell us three quick stories to highlight the unanticipated processes and consequences underlying games:

She wants to make unintentional processes intentional.

Aaron’s story: Boy / Technology / Person

Mary does play tests every week. They ran across a young boy, she’s calling him Aaron. He’s on the autistic spectrum; he would sit silently until a game was present. He could engage with others through a game, and came week after week to play. He started to change. He began to interact with other children through play. This story points to the transformative power of play and how games serve as a framework for broader personal development.

Games were transformative for Mary personally. In the midwest, she says, people play cards and games as a framework for social interaction. We know this online, but it functions historically as well.

Games are older than written language. We don’t know how old they are, but we have evidence from 5870 BC of “A neolithic game Board from Ain Ghazal”.

Mary also shows us a chess board from 1100 AD. Games exist throughout history.

We always hope that technology can make things better. Some are critical. New tech can have un-intentded consequences, and it’s amazing how little we study this.

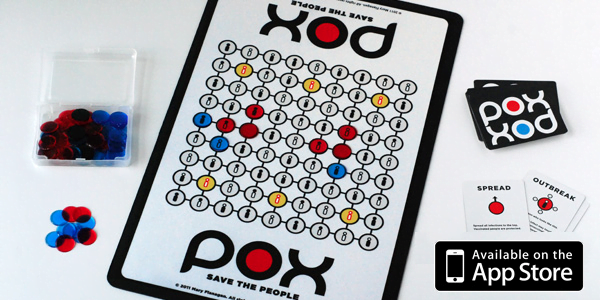

She shows a game called Pox from 2010 that was meant to encourage people to get vaccinated. They produced the game and started studying outcomes. In the game, you learn that vaccination is a smart thing to do compared to using public health to cure people. What’s interesting is what people did and said while they played. They’re producing a paper about this that’s coming out soon.

They made a digital version of POX, then made a Zombie version. Mary has an alternate life as a game publisher, which is kind of weird, although not as weird as people saying “I’m an academic” at game conferences.

They studied two people at time, randomly assigned to pairs, to play Pox.

Subjective Valuation of vaccination were different depending on Digital POX, Analog POX, Zombie POX: the digital version was less effective. Why?

Players played 10-20% faster on the iPod and agreed more. In the analog version, players won 5 out of 6 games, in the digital, they lost 5 out of 6. So they play faster, talk more, and make bad decisions. So this challenges our perception of digitization.

They looked at systems thinking measures, and the results were slightly different. The Zombie POX version performed better, which was a surprise. They didn’t start out to say “Zombie POX will be more convincing! People learn better from the undead!”

That raised a question: what if all the textbooks are fiction?

Next Mary has us play a game: name a person, living or dead, who meets the following criterion (then shows various prompts on slides, for example, “female scientist,” “multiracial superhero,” and so on).

The point of this game is to talk about how games can lead to strange, yet evocative, conversations about race, gender, etc. as players negotiate what counts as a winning category. It’s also about highlighting inequality in STEM.

We lack a collective consciousness about women in science at a deep level. Unpacking the prior issue is that people have biases and stereotypes that are difficult to surpass.

They created a game called “buffalo.” They drew from psychology to look at discrimination levels. Psychologists have standardized studies that look at how people discriminate against one another. It turns out that as we discriminate more, we collapse categories. For example, if I tell T.L. “I’m an artist,” we have a mental image: I wear a beret, all black, have salons, etc. These are old tropes but we still carry them with us. Your first thought wouldn’t be “tennis player,” or “sci fi fan.” Collapsing categories into one dominant way of thinking can be challenged. We can expand the categories and make them more complex.

The more complex your social identity complexity, the less biased you’re likely to be in your daily life. So for example, you wouldn’t assume someone from a particular country is a terrorist.

The research team measured Social Identity Complexity Scores and Average Universal Orientation Scales. They found the game is changing the Social Identity Complexity scores.

Mary showed a picture of people playing the game and tweets from players reporting how bad they felt about themselves. In this way, we can bring discrimination from unconscious level to conscious level.

Then Mary showed a video about subconscious racial bias. Though she’s not sure about the the rigor of the study, it is an example about the complex manifestations of racial bias we have. Stereotypes are persistent. Biases are fluid, but they are real and ongoing.

This leads to big questions: How can people live together, thrive, and find value in difference, rather than pretend that it doesn’t exist?

They are hoping to get Buffalo into middle schools. They have a version of “awkward moment,” based on middle school stories, and another version “awkward moment at work.” These are often based on real world experiences, turned into teachable insights in game play.

They’ve done some systematic studies of the best way to modify bias in terms of the mix of fun, seriousness, and so on.

Designers ask, “How do you choose the right measures?” How can we make a difference, conceptually and empirically? Mary has a background in critical studies, and brings that to game design. Getting back to the idea of human values is one way to do that. Data alone doesn’t let us process what’s happening, but human values do.

In her upcoming book w/ Helen Nissenbaum, they identify trigger points for values. For example, people often assume “values” in games mean “violence,” representation. A values-focused analysis can help us broaden this out.

In Critical Play, Mary talks about Values at Play.

She outlines a few techniques for game design:

- “embedded” technique: switch objects: people buy the game often do not look at the manual, perceiving it merely a game instead a social criticism game

- Importance of framing, iteration

- More diverse team = more diverse games

- Real playtests, all of the time, to prevent “lame studies”

- Learn from audience, not build only that which which we want to play.

She showed a study done by her students about the game Blokus. In the experiment, the only difference across play groups was in the way she framed the game.

For example, when the game was introduced as a “spatial game,” men’s scores go up, and women’s go down, on post-game tests of spatial reasoning. So framing of the exercise, even changed by one word, can have real and differential impacts on outcomes.

Mary’s interested in the question “What is the role of critical inquiry in this process of playful design?” In her lab, they did public engagement workshops. In this game, participants envision and draw what they would imagine their city should look like in the future. She showed a game made by somebody in the project. It is a platformer game where the player, representing a local fisherman, gathers items while evading political figures, against a backdrop of slowly depleting fisheries. It’s called “seaside slums and industrial estuary.”

[…] very active community participation partially because indie game making still retained its cult status.

There is a lot of hype about what games can do, but people wonder can they made their own game. People who don’t know anything about game making can make great critical games.

She shares another studio project, introducing it with the line: “I’ve been collaborating with the Dead!” She produces books with dead poets.

After her father’s passing four years ago, Mary unearthed a set of documents from her father’s “mad scientist” archives.

She shares mockups of installations; she’s trying to realize his inventions. For example, levitating magnets that produce sound, or mic’ing large piezo crystals for sound.

In tiltfactor she’s been doing a lot of projects focused on public health, some of which are critical of the U.S. healthcare system. In the game called “Rethink Health,” they rework the public health system to get participants thinking about the systemic challenge to healthcare reform.

They are reskinning this game to be a plague game, reworking the medieval to renaissance health system.

They also have a handwashing game. It turns out to be a very difficult problem, to get people to change hand washing behavior. The minister of health of Rwanda asked them to do this game. They’re also trying to take some of the principles they’re learning and apply them to other games.

They have a crowdsourced digital humanities project, with the Digital Public Library of America, like Google Image search but they give the data back to the library. It’s a way of people learning about local collections, and bolstering local institutions.

It’s hard to make games be fun when there’s no correct answer. However, it’s fun to think about how such a game can be used to frame critical play.

She ends with a quote from Andre Breton: “What must be changed is the game itself, not the pieces.”

Critical play is widely need in different domains: health care system, [etc.]

Q&A

Q: How to measure a change in behavior, not just bias?

A: The next study is going into measures: social conversation and unconscious responses.

Q: Do unconscious biases correlate with (other things)?

A: We did a study about the buffalo game, they controlled variables such as perceived as a game / not a game, left hand or right handed […]

Q: Can you talk about the difficulty of getting metrics on cultural stuff? Games like Buffalo and Awkward Moment, when you’re trying to change attitudes, behaviors, cultural mores, measuring that change, especially in publicly funded research.

A: It’s a morass. Few studies are longitudinal. Most, even well-done studies, with clean data and random assignment, it’s a 20-minute experiment. It’s a problem with the whole field. In computer science we have interesting progress in gathering data, but biased ways of looking at it. We always have lenses. I’ve found interesting lenses here I want to look through.

Q: Can you talk about any work in the critical game design field regarding how to measure and evaluate media literacies in, say, a community organizing setting. It seems lots of people are doing case studies of workshops, but is anyone doing more controlled experimentation to glean insight from the outcomes of participating in game design? Especially as more and more people do game design, as tools become more widespread and digital games become easier to make. Does taking part in game design change values, say, more than playing the game?

A: We did a session for people to make a game about awkward moments in the industry. In the workshop people won’t finish a game, but hold a discussion about human values.

I find that game design workshops are labour intensive. Unless the workshop is specifically designed for an underrepresented group, it’s a very narrow demographic who is being involved. I had a workshop with age-8 kids but it was difficult to collect data. The Boys and Girls Club actually wanted to do a game design workshop a couple of years ago, but they didn’t have sufficient resources to do it effectively. So we advised against that for them and encouraged them to not even do it because they would get the kind of outcomes they were aiming for.

She’s wanted to make tools to help facilitate game design capacity building, but she has not focused much on measuring that.

Q: What are some emerging trends you seen in how games are becoming helpful or harmful for target audiences?

A: This is a minefield of an area, totally. There are several games that on the surface I would never peg for being, say, male-centric, but upon examining the way the game is framed on the box more ambiguity is introduced. Much of these issues actually stem from advertising tactics who brand a product a certain way, which influences its reception.

Q: How do you split up your mind and practices give the many hats you wear as an artist, academic, designer, etc.?

A: Mary’s practice tends to be team based. She tries to encourage a flat organizational style that looks more like a collective than a big operational team. She likes to explore her interests in many different kinds of venues. For instance, this year she has had many shows in galleries, which is an important world for her, but she also need to balance her time to write books, run workshops, etc.

Ultimately, all of her practices help her meet a particular need as she explores her interests.

Q: Do you do user testing or play testing with your gallery works?

A: No. Except player plays.

Jason: An invitation to make a connection to Fox Harrell! His new book Phantasmal Media is exactly on how bias is built into computational systems. He cites a Clark study from the 50’s, basically the same as the CNN show: kids from different races see a black and white doll, “which one looks nice, which one looks bad?” so it’s unconscious bias and how it operates. Do you know each other? You’re both practitioners and theorists.

A: Yes! Thank you. Good connection.

Q: I was wondering, there seem to be a lot of board games and card games these days, is that a strategy?

A: As an artist, if anyone has done art practice for a while, the studio affects what you make. I was in Italy in a residency, had a massive studio, and made big things. At Dartmouth I don’t have grad students and programmers. I can do paper prototypes, or if a project gets funding. Some of it is access. Having the conversation is really important. We started with values written on cards at a meeting at NYU in 2006. There’s an iPad version of grow a game, but people want the cards. They want to pass them around, lean over, look at them. Also, a lot of the low-income schools I work in, you can’t have everyone networked and whatnot, but they can play it at lunch with cards.

I didn’t come from board game making. I started at Dartmouth. I have a warehouse, and a truck! It’s heavy. I recommend smaller games.

Q: Thank you for your research. I’m concerned about your statement about not designing games for parties. Is it possible for people to play your game outside of classes? People are bombarded with cultural bias, but can only play the game once.

A: Schools often make it available. Lots of people are buying games for parties. We produced these cards, I went to GDC. I was running around with a stack of them. I had game packets, I’d see a friend, give them the cards. Someone else would say “I heard you have these cards, I want to try them out!” I gave them away for free. Then I turned around and saw a grow-a-game pack in the garbage can. So I thought “if they’d paid for that, they would never have thrown it out!” There’s a psychological value of paying for something. It crushes my soul that I can’t just give these away. They’re for sale at cost. I’d love to figure out a model that supports the project.

There is a really great report called “Why So Few” (PDF), which is a longitudinal report for why women don’t go into STEM. The reasons have been clear for a long time, but doesn’t necessarily lead to change. Mary’s work is an attempt to activate that data and get things moving.

Q: When you design systems that highlight biases, how does your approach change according to your understanding of your audience (participants who want to explore their own views, those who are resistant to self-reflection)?

A: Generally, she is not targeting a particular kind of user in terms of “more biased” and “less biased” users. Instead she tracks impact for a broad spectrum of users. Mary has a little formula that places players in different positions: perpetrator of bias, witnesses of bias, etc. We have stereotypes built into culture that reinforce stereotypes. If we can begin to unpack these stereotype threats then you can begin to hear things differently.

Interestingly, we’ve noticed that when we take all the fun, non-“biasy” cards from our game, the impact for reflection automatically gets diminished.

Q: If you take the fun part apart, will people become uncomfortable of what kind people they are?

A: Nobody will admit he/she is a racist.

Q: Any suggestions for practical academic game designer?

A: I will suggest collaborate with someone who know the research method and you will learn a whole new vocabulary. You might want to appreciate your research when you work with someone else. I worked with psychologist after I collected data, data can speak across disciplines.

Q: I playtested a game in a middle school, and pupils ask “is it supposed to be educational?” How to answer for that question?

In my culture, I try to not have the key designers on the front line of playtesting. I will flip it by asking “what do you think.” Only 20% people want to play educational game while 95% will play adventure game. The “educational game” is a terrible frame. Distraction is a good strategy.